Saint Kevin's Church and Graveyard, Camden Row, Dublin City

Now called Saint Kevin's Park, this site has been in religious use since the 1100s

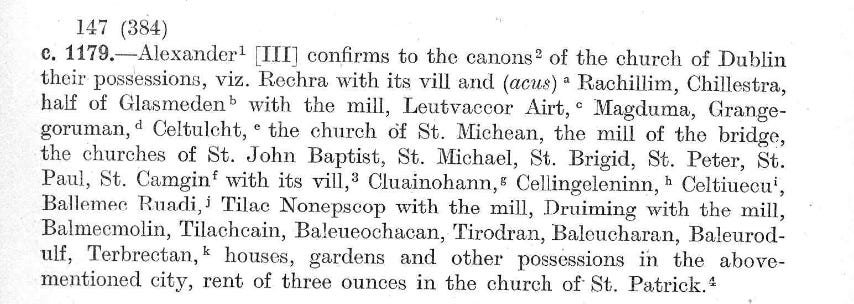

This site is dedicated to St. Kevin of Glendalough (d. 618/622AD). Whilst it is unclear as to exactly when this church was founded, it was listed as part of the possessions of the Augustinian Canons of the Holy Trinity in c.1179.1 In 1191 the church and its lands were granted to St. Patrick’s Church,2 and then came under the direct jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Dublin as part of the Manor of St. Sepulchre.3

In the medieval period St. Kevin’s was located a distance outside of the enclosed city. An excellent historical map showing the location of St. Kevin’s was produced as part of the Irish Historic Towns Atlas volume concerning Dublin (Vol. 1) and can be viewed online here: Map 4, Medieval Dublin c. 840–c. 1540. In H.B. Clarke, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 11, Dublin, Part I, to 1610.4

Today St. Kevin’s is a well maintained public park in the center of Dublin, only a short walk from St. Stephen’s Green. It is just around the corner and behind the well known music venue and pub; Whelan’s. Previously in the shadow of DIT’s Kevin Street campus, these buildings have recently been demolished as part of an ambitious redevelopment plan.5

St. Kevin’s fortunes waxed and waned over the years, falling into ruin and being repaired on a number of occasions over several turbulent centuries. After the reformation, St. Kevin’s came into the hands of the Church of Ireland and operated as a parish, eventually becoming part of St. Peter’s COI parish and serving as a church of ease.

In 1582 the church was re-roofed6 but ‘fifty years later it is described in Archbishop Bulkeley's account of the diocese as "both church and chancel altogether ruinous”’.7

St. Kevin’s is best known as the burial place of the catholic martyr Archbishop Dermot O’Hurley. His entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography is worth reproducing in full:

O'Hurley, Dermot (c.1530–1584), catholic archbishop of Cashel and martyr, was the son of William O'Hurley, a servant to the Fitzgerald earls of Desmond, and his wife Honora O'Brien. He was born near Emly, Co. Tipperary, but his family later moved to Lickadoon, Co. Limerick. Little is known of his early education in Ireland, though he may have attended the cathedral school at Emly. He continued his education at the university at Louvain, where in 1551 he graduated MA from the Collège du Lis and, having won renown for his commentaries on Aristotle, was appointed professor of philosophy at the college in 1559. He also became a doctor of civil and canon law, and dean of the College of St Ivo; he probably left Louvain about 1564. He then spent four years as professor of law at Rheims university, before moving to Rome c.1568, where he may have continued his academic career. Claims that he was a member of the holy office (the inquisition) while in Rome come from partisan sources; at most he may have given occasional legal advice. During his time at Rome, he urged the papacy to support an invasion of Ireland to end the persecution suffered by catholics there, and in 1581 acted as interpreter for a representative in Rome of the rebel leader James Eustace (qv), Viscount Baltinglass.

In 1581 Pope Gregory XIII decided to appoint O'Hurley to the archdiocese of Cashel, though he was still a layman. Gregory issued a papal brief in his favour on 15 July, and O'Hurley received the clerical tonsure and was advanced to the four minor orders and three major orders by Thomas Goldwell, bishop of St Asaph, within the space of sixteen days: he received the tonsure on 29 July, and was made ostiary, lector, and exorcist on 30 July, acolyte on 1 August, subdeacon on 6 August, deacon on 10 August, and priest on 13 August. He was provided to the archdiocese of Cashel on 11 September at the secret consistory, and was granted the pallium in person on 27 November 1581. His appointment was due to his family's closeness to the earls of Desmond, the 15th earl, Gerald Fitzgerald (qv), being then in rebellion against the crown. O'Hurley was commissioned to take papal letters to Desmond encouraging him to remain steadfast in his rebellion.

After leaving Rome in summer 1582, O'Hurley reached Rheims in August, where he fell seriously ill; he was not well enough to finish his journey home until August 1583. At the port of Le Croisic at the mouth of the Loire, he gained passage to Holmpatrick, near Skerries, Co. Dublin. He sent a bundle of documents and with them his pallium to Ireland by a different ship, which was intercepted by the authorities. On his arrival in Ireland in the summer of 1583 he was met by Father John Dillon, who took him first to Drogheda, where they feared they had been discovered by a government informer. They hastened to Slane castle where Dillon's relative, Thomas Fleming, Baron Slane, provided sanctuary for them. O'Hurley hid for a time in a secret chamber at Slane castle; he ventured out from Slane to Cavan to visit some priests he had known from his time on the continent. Sir Robert Dillon (qv), chief justice of the common pleas, on a visit to his cousin for dinner, spoke with O'Hurley, who posed as a guest. Dillon's suspicions were aroused by O'Hurley's learned manner and, after making further inquiries, he uncovered the archbishop's true identity.

By that time, however, O'Hurley had travelled to Carrick-on-Suir, Co. Tipperary, where he met Thomas Butler (qv), 10th earl of Ormond. O'Hurley's arrival in his lordship put Ormond in a difficult position. Although a protestant, all of his family, tenants, and supporters were catholic and he allowed them the freedom to worship according to their religion. However, royal officials in Dublin, long jealous of his favour with the queen, watched Ormond closely, eagerly awaiting the chance to expose his covert support for catholicism. Ormond appears to have agreed to protect O'Hurley as long as he avoided meddling in political affairs and stayed in Co. Tipperary. After this meeting O'Hurley visited the site of Holy Cross abbey. He wrote to the Church of Ireland archbishop of Cashel, Miler Magrath (qv), on 20 September 1583, suggesting that they tolerate each other's activities in their competing jurisdiction. However, Ormond, to whom O'Hurley had entrusted the delivery of the letter, retained it as he distrusted Magrath (it is now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Carte 55, fol. 546).

In the meantime, Baron Slane had been summoned before the lords justices in Dublin, where he was berated for sheltering a catholic archbishop and ordered to apprehend O'Hurley. Slane hurried to Carrick, where he and Ormond concluded that O'Hurley had to be sacrificed: it is uncertain whether Ormond and Slane betrayed O'Hurley to the authorities or merely persuaded him to surrender himself. If O'Hurley went willingly, it suggests that he overestimated Ormond's ability to protect him and underestimated the ruthlessness and anti-catholic zeal of the authorities. In the event he was led in chains to Dublin by Slane and imprisoned at Dublin castle on 7 October.

He was interrogated by Edward Waterhouse (qv), a member of the Irish council, between 8 and 20 October 1583; he admitted having met in Rome Richard Eustace, brother of the rebel Viscount Baltinglass, but denied bringing letters to Desmond and other rebels. The lords justices, Adam Loftus (qv), Church of Ireland archbishop of Dublin, and Henry Wallop (qv), vice-treasurer of Ireland, then sent to Whitehall for instructions and were told on 10 December to use torture. They were reluctant to do so, knowing that it would quickly become public knowledge in Ireland, and requested that he be tortured in London instead. After receiving further orders from London, they put O'Hurley to torture around the beginning of March 1584, dressing his feet in boots containing boiling oil and tallow and placing them over a fire, with the result that the flesh came away from the bones. The ordeal nearly killed him. O'Hurley displayed great strength of will by refusing to divulge any information or to incriminate Ormond despite being urged to do so. He was then offered high ecclesiastical office in the Church of Ireland in return for renouncing his faith, but remained unyielding.

On 8 March 1584 guards discovered letters written by O'Hurley from prison to Ormond and a relative. At this point the lords justices became very agitated and requested permission to execute O'Hurley by martial law, believing that he would be acquitted if he were tried by common law. Ormond was then at the royal court and they feared that O'Hurley would alert Ormond to their efforts to implicate him in treason. On 28 April they received instructions from Thomas Walsingham, secretary of state to Elizabeth, tacitly authorising them to try O'Hurley by martial law. However, they delayed, knowing that the execution would be controversial. They waited until Sir John Perrot (qv) arrived in Dublin in June to take up the lord deputyship of Ireland and, having secured his approval, sentenced O'Hurley to death by martial law on 19 June. He was hanged at Hoggins Green the next day; the execution was carried out in the early hours of the morning to avoid attention, but a group of archers happened to be practising on the green, thwarting the authorities’ efforts to suppress reports of the martyrdom. O'Hurley's remains were recovered by citizens of Dublin and interred at St Kevin's church, while his clothes were kept as relics. In a very short time he was acclaimed throughout Ireland as a martyr for his faith, and his burial place became a shrine for Dublin catholics. Archbishop O'Hurley, along with sixteen other Irish martyrs, was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 27 September 1992.

Sources

Brady, Ir. ch. Eliz.; The analecta of David Rothe, bishop of Ossory, ed. P. F. Moran (1884), pp. xiii–xlvi; Benignus Millet, ‘The ordination of Dermot O'Hurley, 1581’, Collect. Hib., xxv (1983), 12–21; NHI, ix, 354; William Hayes, ‘Dermot O'Hurley's last visit to Tipperary’, Tipperary Historical Journal (1992), 163–73; J. J. Meagher, ‘The beatified martyrs of Ireland (3): Dermot O'Hurley, archbishop of Cashel’, Ir. Theol. Quart., lxiv (1999), 285–98

Writing c.1618, Archbishop David Rothe8 wrote that due to the level of pilgrimage and reported miracles at Archbishop O’Hurley’s grave at St. Kevin’s, that the church had been rebuilt and beautified:

Pius martyr in vireto prope vrbem suspensus, postquam sacram exhalasset animam, in vicino oratorio S. Keuini semidiruto sub vesperam fuit sepultus : ad cuius tumulum diuersa fcruntur edita miracula, ob quae in venustiorem formam vetusta Ecclesia instaurata est, additis muris, & apertft via frequentanti populo, qui se commendare solet orationibus & suffragijs sancti Martyris.

The pious martyr, suspended in a green field near the city, after he had breathed out his last breath, was buried towards evening in the nearby half-ruined oratory of St. Kevin: at whose tomb various miracles were reported to have occurred, for which reason the ancient church was restored to a more beautiful form, with added altars, and the way was opened to the frequenting people who are accustomed to commend themselves with prayers and the intercessions of the holy martyr.9

Despite any such repairs, by 1630 the nave and chancel had fallen once again into ruin.10

A modern memorial to Archbishop Dermot O’Hurley is located beside the church ruin.

In 1698 St. Kevin’s was offered to the Huguenot community for their use as a place of worship.11 Unfortunately, nothing now remains above ground of the medieval church. The T-plan building today dates from the mid eighteenth century and seems to have been built on the foundations of its medieval predecessor. The Duke of Wellington was baptized here in 1769, the font from which is now in St. Nahi’s church in Dundrum.12 It fell into ruin around the beginning of the twentieth century and became the centerpiece of a new public park.

The National Inventory of Architectural Heritage describes the church as follows:

Freestanding T-plan ruined Church of Ireland church, built c. 1750, comprising nave and north transept. Now roofless and ruinous. Graveyard now in use as public park. Uncoursed rubble calp limestone walls. Squared roughly-dressed pedimented limestone belfry atop entrance (west) elevation, having dressed limestone coping and round-headed opening with dressed limestone voussoirs. Round-headed window openings having squared calp limestone voussoirs, granite sills and some steel panels inset. Triple arrangement of round-headed window openings to east gable. Round-headed doorway to west gable, with tooled calp limestone voussoirs and recent gate, and having round-headed window above. Grave-slabs to floor to interior.13

Despite the changes after the reformation, the graveyard remained in continuous use by Catholics right up until the 1820s when protestant Archbishop William McGee, a fervent supporter of the ‘second reformation’,14 and opponent of Catholic emancipation, forbid the usual graveside prayers in an episode that gave rise to much outrage. William John Fitzpatrick, in his ‘History of the Dublin Catholic Cemeteries’ wrote the following account:

In 1823, a series of slights which had latterly been offered to the Catholics reached its height when Archdeacon Blake, in St. Kevin's churchyard, was rudely interrupted while offering a prayer over the grave of Mr. Arthur D'Arcy, a prominent citizen of Dublin, and brother of Mr. John D'Arcy, D.L., afterwards Lord Mayor. He had been a very charitable and popular man, and his sudden death, by a fall from his horse, excited much sympathy. The muster at his funeral was naturally large. Priests, wearing scarfs and hat-bands, walked in solemn procession up the lane by which the churchyard is reached from Kevin Street. On approaching the grave they gradually encircled it, so as to recite the " De Profundis " and other prayers usual on such occasions. All persons in attendance stood uncovered, and the Rev. Michael Blake, Vicar General, was about to speak when— but he must be allowed to tell his own tale.

" I did nothing," writes Dr. Blake, afterwards Bishop of Dromore; "nothing which any layman might not lawfully do nothing which has not been done by Catholic clergymen and Catholic laymen under the administration of the most bigoted prelates, and during the most persecuting periods of former times.

" Yielding to the request of a near and venerable relative of the deceased, I took off my hat to assuage by a short con doling prayer the sorrows of the living — to implore perpetual rest and peace for the departed soul ; and at this moment, and without any other provocation, an order of Dr. Magee, the Protestant Archbishop, was rung in my ear, that I must not offer any prayer over that grave ! Gracious heavens ! Is there a country in the universe so degraded as Ireland?"

Dr. Blake goes on to say that, to avoid any unseemly disturbance which might arise out of indignation likely to be ex cited by this interference, he mentioned in a low voice to the few afflicted friends who were immediately at his side or before him, that he had been warned, on the authority of the Protestant Archbishop, not to say any prayers there ; he recommended, at the same time, that, as the Catholics present could not conform to their usual custom without appearing to resist authority, each one would offer his prayer for the deceased silently ; and he expressed a hope that their resignation under the unexpected additional trial would render their prayers more acceptable before God.

Dr. Blake's immediate companions at the grave were tranquillised by these words ; and his prudent line of conduct pre vented the large concourse who attended the funeral from knowing of the transaction until all danger resulting from excited feelings had passed away. The priests led the way, in the same order that they had entered, and in a few moments the sexton stood in solitary possession.

A Protestant who was present addressed to the Freeman's Journal, of September loth, 1824, a letter of warm protest and sympathy.

Thanks to Dr. Blake and his sympathisers, a deep impression was produced. It had long been believed that an Act of Parliament stood in the way of any reform of the grievance; but O'Connell declared that he would "drive a coach-and-six" through it.

Daniel O’Connell, galvanized by this and other similar anti-Catholic episodes, led a legal and popular agitation against the efforts of Archbishop William McGee which ultimately resulted in the establishment of Golden Bridge and Glasnevin Cemeteries.

Unfortunately, it seems when the graveyard became a park that the majority of the gravestones were cleared and paced against the graveyard walls, and the church itself. Photographs and transcriptions of many of the headstones may be viewed on the Ireland Genealogy Projects Archives website.15

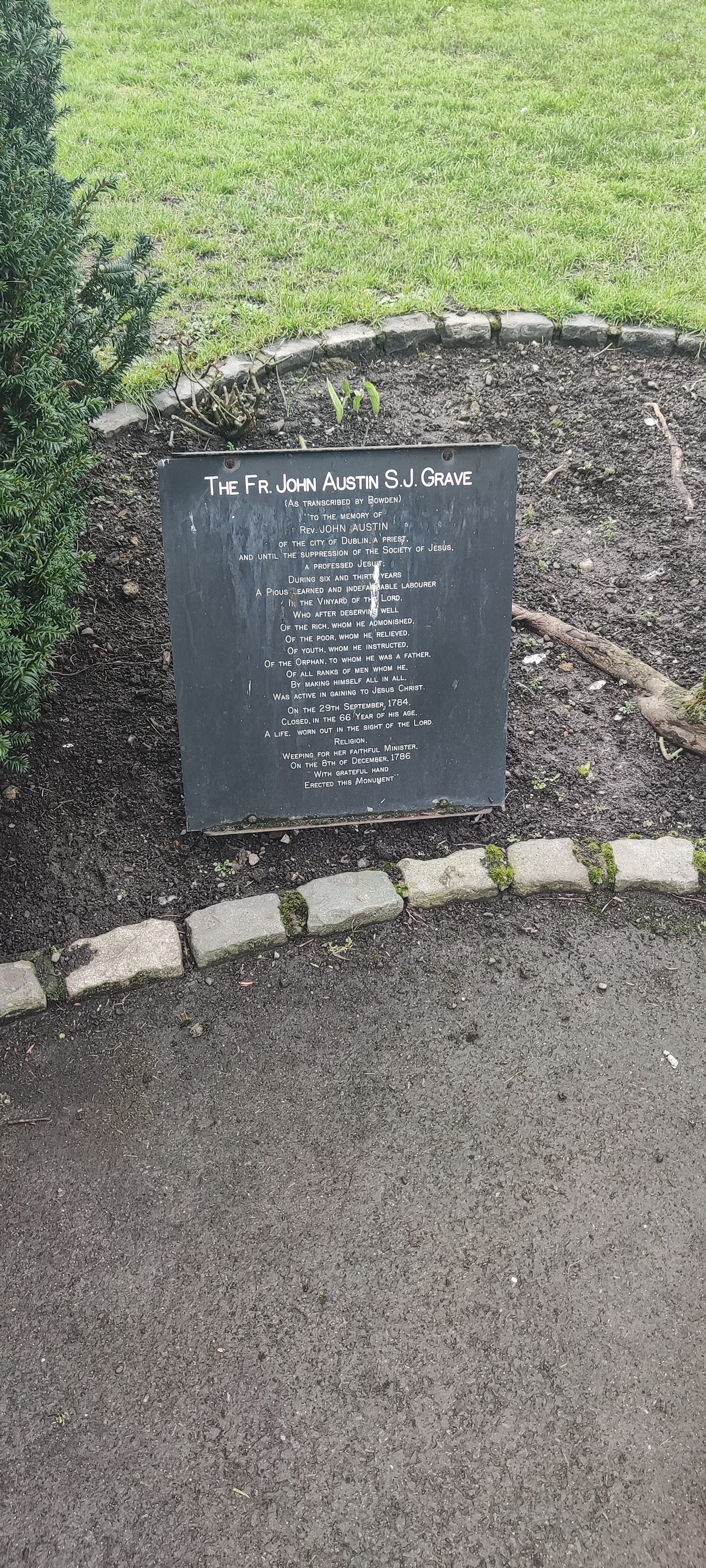

There are a number of prominent memorials in the graveyard, chief among these is that of Fr. John Austin S.J16 (1717-1784). Father John Austin was a prominent educator and preacher who was evidently much loved by the Catholics of Dublin. It is quite remarkable that such a prominent memorial to a Catholic priest was erected in the eighteenth century.

St. Kevin’s is fully enclosed by walls and railings, the entrance gate is a quite striking and unexpected sight to come across when walking down Camden Row. St. Kevin’s is well maintained by Dublin City Council and there are set opening hours which are published on DCC’s website here: https://www.dublincity.ie/residential/parks/dublin-city-parks/visit-park/st-kevins-park. I highly recommend visiting, an ideal place to have a coffee and sit awhile - there are plenty of benches.

This reference is taken from the narrative included on the entry for the site on the National Monument Service’s Historic Environment Viewer, SMR DU018-020078- Link: https://heritagedata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=0c9eb9575b544081b0d296436d8f60f8&query=18a4b61b268-layer-9%2CSMRS%2CDU018-020078-

The Calendar of Archbishop Alen's Register is cited as the source, and the following appears to be the relevant extract on page 7:

My guess is that St. Camgin is a corruption of the Old Irish word for Kevin. Note the reference to the church’s “vill” - this is an estate or manor.

RSAI AlenRegister, 'Calendar of Archbishop Alen's Register'. Accessed on Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland <https://virtualtreasury.ie/item/RSAI-AlenRegister> (17 February 2024). Repository: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland.

pp 19, RSAI AlenRegister, 'Calendar of Archbishop Alen's Register', accessed on VRTI (17 February 2024).

James Mills and Gertrude Thrift, The register of the parish of St Peter and S. Kevin, Dublin, 1669-1761 Dublin (Dublin, 1911), p. iv. Accessed 18/02/2024 here: https://archive.org/details/registerofparish00dubl/page/n9/mode/2up

The analecta of David Rothe, bishop of Ossory, ed. P. F. Moran (1884), pp 437. Accessed 17/02/2024 at https://archive.org/details/TheAnalectaOfDavidRotheBishopOfOs/page/n637/mode/2up?q=1609

Latin translation via ChatGPT.

Stout: https://heritagedata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=0c9eb9575b544081b0d296436d8f60f8&query=18a4b61b268-layer-9%2CSMRS%2CDU018-020078- It is not clear as to the exact reasons why the church became ruinous, whether it was neglect, or some more dramatic reason.

Chesser, Cormac (2022) From Persecution to Commemoration – the French Protestant Community in Eighteenth Century Dublin, c. 1680 – c. 1815. PhD thesis, National University of Ireland Maynooth, pp. 17-18. Accessed 18/02/2024 here: https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/17344/

For more on Fr. Austin: O’Rahilly, A. (1939). Father John Austin, S.J. (1717-1784). The Irish Monthly, 67(789), 181–196. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20514501