St. Colmcille's Well, Calliaghstown, Co. Meath

History, discussion, folklore and photographs of this remarkable Holy Well near Drogheda

Located on a surviving segment of the old Julianstown to Duleek road, in the townland of Calliaghstown in County Meath, is a rather striking example of a Holy Well, said to be associated with Saint Colmcille. So many Holy Wells are now, to the untrained eye, little more than ditches, hollows, or puddles. This Holy Well however, is impossible to miss and it has some very interesting features. Before visiting I had envisioned taking a few quick pictures, then forgetting about it and moving on - another minor antiquity photographed and documented. After visiting I felt the need to find out more so I have spent quite a few hours over the past number of weeks researching the history and folklore of this well. But more on that later, firstly lets set the stage by having a quick look at what exactly a "Holy Well" is.

There are thousands of Holy Wells in Ireland, some estimates put it at more than 3,000. Certainly, it is likely that within the boundaries of your own local parish or townland there was a Holy Well at some stage - although little or nothing may remain today. The term "well" is used somewhat loosely here, as the "wells" in question are often natural springs or sometimes merely hollows that can fill with water. While the form of the Holy Well may vary, what is common about them is that they are Christian ritual sites dedicated to a venerated religious figure, most often a local or universal Saint (although sometimes to God).

Holy Wells often have a miraculous origin story, formed by a Saint's tear, a strike of his staff or as an answer to a prayer. Sometimes they were preexisting wells, from which a Saint drank or used to baptize people and thus through this association the wells became "holy". Indeed, some of these wells may have been venerated sites long before the coming of Christianity and, through an association with an early saint, became absorbed and integrated into the new religion and lost their pagan meaning.

More often than not there are miracles associated with Holy Wells and their water, especially the miraculous curing of specific ailments such as headaches, eye issues or fertility to name a few. People would visit the Holy Well to pray for a cure, sometimes drinking, washing with or otherwise using the water. Votive offerings were frequently left and today at some Holy Wells we can see this practice still, with pins, money, rosaries, icons, rags etc. being left as ritualistic offerings. Holy Wells were a place of pilgrimage from medieval times with the largest pilgrimage typically occurring on the feast day associated with the patron saint of the well - this pilgrimage being known as the "pattern day".

The "pattern" would involve preforming various prayers and stations as well as being a celebratory event. Holy Wells increased in importance after the protestant reformation when Church property was seized. They became particularly important during the penal years when Catholics were subject to great oppression and unable to worship as openly as they once did. Holy Wells served as a tangible link to the faith for the Catholic masses in the era of the mass rock and priest hunter.

It was the "celebratory" aspect that led, in modern times (19th century onward) to the large scale decline and suppression of the pattern days. This followed on from Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the repeal of the worst of the penal laws. Dismayed by the excesses associated with the celebrations, in particular the alleged over-consumption of alcohol, Parish Priests and Bishops banned the pattern days and it naturally followed that some Holy Wells became neglected and abandoned. This was part of a centralized push by the Church hierarchy to move the focus of religious expression from the community into the large, new Churches which were springing up all over the country.

Looking further back however, it is clear that pilgrimage formed a major part of religious life in medieval times, and that Holy Wells formed a vital cog in this. They were the "local" destination that everyone in the area would be able to visit, in a time when people would live their entire lives with a few miles of their birthplace. There is much to said about pilgrimage in medieval Ireland but I think the brief amount I've mentioned should provide sufficient context for our present discussion of our specific well. For more on pilgrimage I recommend Louise Nugent's "Journeys of Faith: Stories of Pilgrimage from Medieval Ireland" which I recently reviewed on this site.

Saint Colmcille (Columbkille, or St. Columba as he is also known), is one of the three patron saints of Ireland, along with Saints Patrick and Brigid. A descendant of Niall of the Nine Hostages, he founded many monasteries in Ireland and, after he left Ireland and entered into exile on the isle of Iona, in Scotland. You can read more about St. Colmcille here and here or indeed Adomnán's Life of Columba - a hagiography which dates from the 7th Century - is a very interesting read. Suffice it to say, Colmcille, the "Dove of the Church" may, as O'Riain puts it, "justly be regarded as the single most important native Irish saint".

St. Colmcille's Well, Calliaghstown, Co. Meath

St. Colmcille's Well in Calliaghstown, Co. Meath is said to have curative properties for those with warts and sores. The legend is (according to an entry in Dúchas Schools' Collection) that the well became holy when St. Colmcille, on a journey to visit a friend and suffering from great thirst, came across the well, drank from it, and subsequently blessed it. Like many Holy Wells, it is said to turn angry when abused. A story goes that when a local person diverted the water for use in a bleachery the well became infested with redworm rendering it useless to all. The well only returned to normal after a legal case ensured that the flow of water was restored to the way it was before. Apparently the well was also the scene of dances on summer Sunday evenings when a piper would come from Drogheda to play and large amounts of locals would gather.

St. Colmcille's Well is located in Calliaghstown Co. Meath on a surviving portion of the old Julianstown to Duleek road. The Julianstown to Duleek portion of the R150 was greatly upgraded between 2006 and 2008. The satellite images below show the location of the well and the topography of the area before and after the construction of the new road. Happily for the visitor, the construction of the new road means that the road on which the well sits on is now very peaceful and quiet.

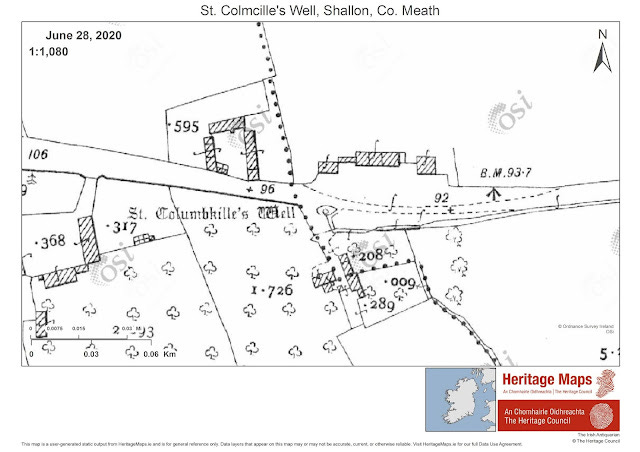

During the course of my research for this piece it became noticeable that the name of the townland in which the well is located kept changing between Shallon (in older references) and Calliaghstown. Both seem to be used interchangeably. This is due, no doubt, to the fact that the well is close to the border between the two townlands. The 25 inch OS map below demonstrates this, the border between the townlands is marked by a dotted line. But for those keeping score, the well is officially in Calliaghstown!

All the modern sources state that the well Co. Meath is dedicated to St. Colmcille. Cogan for instance, writing in 1867, tells us that "On the townland of Shallon, Parish of St. Mary's Drogheda, in the neighborhood of Duleek, there is a holy well dedicated to St. Columba which in modern times was much frequented on his festival day". Intriguingly however, while searching for early references to the well the dedication of the well is perhaps called into question at first glance.

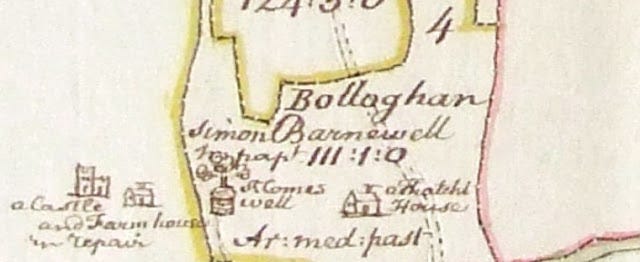

The earliest reference I can find to the Holy Well at Calliaghstown is in the map and terrier of the Down Survey. The Down Survey was a massive mapping project conducted by William Petty in 1655 and 1656. Its purpose was to identify the extent and ownership of land following the Cromwellian conquest. This was in order to facilitate the wholesale expulsion of the owners ("to hell or to Connacht") in order to reallocate the land to Cromwell's soldiers in lieu of cash as payment for their service. Despite the Down Survey's disturbing origin and purpose, it serves today as a very valuable and informative historical document which has been fully digitized and made publicly available. As well as maps, there is also a textual component called a "terrier" to go with the map which gives further detail. On examining the Down Survey for mention of our well I noticed two entries, reproduced below, on both the map and terrier.

Here we can see a drawing of the well on the map, but it is called "St. Come's Well".

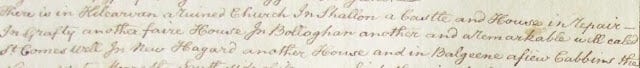

"In Bolloghon... ...a remarkable well called St. Comes Well" So says the text of the terrier that accompanies the above map.

Despite being called St. Come's Well I feel there is a little doubt that the well referred to is our well, that is, St. Colmcille's well. In the Down Survey Calliaghstown is referred to as Bolloghon. Despite the plurality of Holy Wells I think it unlikely that the one townland should have two such remarkable wells! It must be said that by no means am I the first to notice this entry, Noel French in his excellent book Meath Holy Wells mentions it, but doesn't discuss it further.

This leaves us with the question of why the different name? Here we enter the realm of supposition and, for the want of a better word, guesswork. It could be that "St. Come" is a corruption of some version of Columba or Colmcille ('Colm' or 'Columb' to 'Come' perhaps?). In trying to clarify this I looked for similar corruptions elsewhere, and I found that there is another Holy Well in Scotland that was formally detailed on a map as St. Come's well and is attributed to St. Colm (Colmcille).

During my research I found that there was indeed a St. Come (St. Comus of Scotland) who was contemporaneous with St. Colmcille. St. Come shares the same feast day as St. Colmcille, the 9th June, which is the traditional day of the pattern at the well in Calliaghstown. There is scant detail available on this saint, the most comprehensive account I could find being that detailed by John O'Hanlon in Vol VI of his Lives of the Irish Saints (pg 610):

St. Come, or Comus, Abbot. [Sixth Century] In Adam King's Kalendar, at the 9th of June, is entered the feast of a St. Come, said to have been Abbot and Confessor in Scotland, under King Aidanus. Also, he is commemorated by Dempster, in his Menologium Scotorum, as an Abbot, at the same date. He must have flourished in the time of St. Columkille, who was contemporaneous with King Aidanus. He is also alluded to by Camerarius as an Abbot, and by the Bollandists at this date.

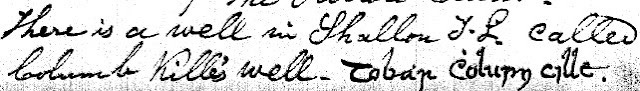

While it is tempting to jump to the conclusion that somehow the well at Calliaghstown was originally dedicated to the obscure St. Come of Scotland and, through the passage of time, has become erroneously attributed to his more famous contemporary Colmcille, I think this very unlikely. St. Come, while contemporaneous with Colmcille, and for all we know knew him in Scotland, has no known association with Ireland. There is a large body of folklore about St. Colmcille's association with the Callaighstown well (more on that later) and the entry in the Ordnance Survey Letters for County Meath from the mid 19th Century gives us the name of the well in Irish, again confirming Colmcille as the patron saint.

It seems clear we must accept that the well in Calliaghstown has been dedicated to St. Colmcille for hundreds of years and that, alas, we must allow St. Come of Scotland to return to his quiet rest from which he was unnecessarily disturbed.

I visited the St Colmcille's Well in Calliaghstown, County Meath on a hot day in late May 2020, following a period of very fine, hot weather. The well, and the surrounding foliage, seemed to have been recently "tidied" and the site was in general good order.

St. Colmcille's Holy Well is located on the side of the road and is a quadrangular construction with flower beds either side. From the road the well "basin" itself is not visible, rather, what you see somewhat resembles the back of a wall. Immediately noticeable however, is a significant crack in the brickwork.

The view of the St. Colmcille's Well from the road. What is noticeable, aside from my bicycle, is the worrying crack in the brickwork. The steps down to the front of the well are on the far left of the photograph.

At the side there is a short series of steps down which one descends to the "front" of the well. It is said (Dúchas Schools' Collection) that pilgrims would make their way around the well in a circle, over these steps, on their knees, as part of the "stations".

Once we come around to the "front" of the well we can see what makes this Holy Well so "remarkable". Across the foreground a large lintel restricts access to the well itself. It is said (again, Dúchas Schools' Collection) that the wall around the well was constructed so as to protect it from cattle. Located in an arched niche in the back wall is a carving of a solitary figure.

The well basin itself had a significant amount of water in it, although markings on the surrounding brickwork suggested that the water levels were lower than they had been, no doubt due to the very dry weather. Sadly, there was a degree of foliage in the well basin. If this was carefully removed the appearance of the well would be greatly improved. The crack observed on the "roadside" side of the well is clearly visible from the front of the well also, the crack runs through the wall. This damage is certainly a cause for concern and needs to be repaired before it gets any worse. Should this damage be left unaddressed, it is possible that the stability of the wall could be compromised to such an extent that the wall could collapse. This would be disastrous, as the fine carving would certainly be broken.

Moving on to the carving, it is not immediately clear who is depicted. One would assume it is a depiction of St. Colmcille, but for the fact that the fine quality and execution of the carving looks very out of place compared to the rest of the well. Initially upon viewing it I assumed it depicted an abbot of some sort with a form of biretta on his head. During the course of my research I came across an article by John Bradley who writes that rather than St. Colmcille, or even an abbot, the figure depicted is a king or some other royal figure, and my biretta is rather a crown.

The figure is that of a male dressed in a long pleated tunic and overtunic which is belted at the waist. Over his shoulders is a mantle centrally fastened beneath the neck. The left arm is extended and holds the edge fold of the mantle while the right arm is flexed below the chest. The head is slightly turned and bears a crown with small tufts of hair projecting beneath. On the feet are slippers with pointed toes. The figure forms part of a panel with a semi-circular top, bordered by a roll moulding which is ornamented with an incised band. The whole piece is freestanding and the figure has a maximum height of 1.00m, a maximum width of 55cm, and a maximum depth of 16cm.

Bradley reports that, according to a local, until approximately 1925, the figure faced onto the road, but had to be turned to its current position due to the stone-throwing of passersby. This could explain the broken and missing left hand.

In the course of my research, I looked for early drawings or photographs of the well in its original orientation, but was unable to find any. I did, however, come across two excellent photographs, undated, but taken no later than the 1930's. They were included in an entry in the Dúchas Schools' Collection. In the photographs we see that the well has not changed massively, but there are some differences. The buildings in the background are now in ruins. Obscured by trees and bushes only their shells remain. The two large trees (which must have been of a considerable age at the time the photographs were taken) which stood on either side of the well are gone - we find only flowerbeds today.

Bradley goes on to state that he thinks that the royal figure may be one of the magi, or three kings. I am no expert, and with the weathering and poor lighting it is difficult, (oblique lighting would show up greater detail) but it appears to me that the flexed right arm may have the palm of the hand turned upwards supporting some item. Bearing gifts? I will leave determining this to the experts.

Sociologically, one could argue that it is who the people thought it was that really matters - it is clear that for hundreds of years people have viewed this figure as being a depiction of St. Colmcille - but we can be relatively sure that this figure was not originally intended to depict Colmcille.

So if the figure was not originally that of St. Colmcille, it must follow that it is not original to the well. Certainly, the level of ornateness and sophistication of the carving suggested this in any case. If the figure is that of one of the magi, or three kings, it is likely that it was not intended as a stand alone piece, but rather to be a part of a larger scene, likely the Adoration of the Magi (when the three kings, or three wise men, guided by the Star of Bethlahem, visited and presented gifts to the newborn Christ). Bradley's article also informs us that the stone of the carving is made from English oolite, probably manufactured and imported before 1400AD (Bradley dates the carving to around 1300AD). Such a carving would have been imported not for a well, but rather for a larger religious foundation such as an abbey or some form of monastery.

This leaves us with the question of where the carving was taken or moved from, and why. The answer may lie in the name of the townland in which the well is located, Calliaghstown. The Irish word 'Cailleach" can be translated as meaning 'nun' a religious sister. Calliaghstown is derived from this word, so we can suppose that the townland must have had some association with a religious foundation of nuns. An examination of the excellent Logainm website confirms this, with references to records dating back to 1540 of a house of Nuns. Bradley writes:

Brady has suggested the existence of an Arroasian nunnery here in the 12th Century, which later became the part of the possessions of Odder... ... It is possible that this statue was commissioned originally for the Calliaghstown nunnery and was reset in the wall sometime after the Dissolution.

I feel it to be a logical conclusion that it was moved from somewhere nearby, as it would have been difficult, unlikely, not to mention dangerous, to move the carving from a long distance away to adorn a (remarkable though it may be) mere well. The area surrounding Calliaghstown, being close to Duleek and Drogheda, had a significant number of religious foundations and buildings dating back to the 13th, 14th and 15th Centuries. It could, perhaps, have been rescued from any of these in the surrounding area following the Dissolution, or Suppression, of the Monasteries by Henry VIII in the mid 16th Century.

Returning to the well itself in general, it is clear from the Down Survey that it was well established and impressive by the time of the Cromwellian conquest. It is not too much of a leap therefore, given the integration of the carving sometime after the Dissolution, to suppose that the well may have become a focal point for worship in penal times and had been in existence for many hundreds of years before that.

While St. Colmcille's Well it is no longer actively venerated in the same manner as some Holy Wells are (there is no evidence of rags or offerings at the well, or record of modern pilgrimage) it continues to be recognised in recent times as a religious, venerable site, reflected in the usage of water collected from the well in processions at Mass on special occasions in St. Mary's Catholic Church in nearby Drogheda.

To conclude, this site is well worth a visit, it is a designated National Monument in good order (aside from the worrisome crack in the brickwork) and the quiet location makes for a peaceful visit. Aside from possibly one of the residents, you are likely to have the place to yourself. It is a perfect stop off point on the way to the more substantial medieval remains at nearby Kilsharvan, Duleek or Drogheda.

References and Further Reading

Journal Articles

A Medieval Figure at Calliaghstown, County Meath, John Bradley, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 110 (1980), pp. 149-152 (4 pages)

The Holy Wells of Meath, John M. Thunder, The Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, Fourth Series, Vol. 7, No. 68/69 (Oct., 1886 - Jan., 1887), pp. 655-658 (4 pages)

Paying the Rounds at Ireland's Holy Wells, Celeste Ray, Anthropos Bd. 110, H. 2. (2015), pp. 415-432 (18 pages)

Maps

https://www.heritagemaps.ie/WebApps/HeritageMaps/index.html (OSI Maps). https://www.google.com/earth/ (Satellite images). http://downsurvey.tcd.ie/

Other Blogposts/Websites/Links

https://www.logainm.ie/en/38433

https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/5008890/4964139/5079578

https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/5008904/4965505

https://www.independent.ie/regionals/droghedaindependent/localnotes/moving-from-history-to-modernity-at-st-marys-church-27118430.html

https://www.teanglann.ie/en/fgb/cailleach

http://www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/digital-book-collection/digital-books-by-subject/ordnance-survey-of-irelan/

https://saintsplaces.gla.ac.uk/place.php?id=1315823686https://www.libraryireland.com/biography/SaintColumcille.php

https://celt.ucc.ie//published/L201040/index.html

https://www.catholicireland.net/saintoftheday/st-colmcille-of-iona-521-597-3rd-patron-of-ireland/

Books

Seward, William Wenman, 'Topographia Hibernica, Or The Topography of Ireland, Ancient and Modern' (Dublin, 1797).

D'Alton, John, 'The History of Drogheda With its Environs Vol II' (Dublin, Published by the Author, 1844).

Cogan, Rev. Anthony, 'The Diocese of Meath, Ancient and Modern Vols I & II' (Four Courts Press 1992, first published in 1862 & 1867).

O'Hanlon, John, 'Lives of the Irish Saints Vol VI' (1873).

Pochin Mould, Daphne D. C., 'The Irish Saints: Short Biographies of the Principal Irish Saints from the time of St. Patrick to that of St. Laurence O'Toole' (Clonmore and Reynolds Ltd, 1964).

'Archaeological Inventory of County Meath' (Dublin: Stationery Office, 1987).

French, Noel, 'Meath Holy Wells' (Meath Heritage Centre, 2012).

Ó'Ríordáin, John J, 'Early Irish Saints' (2016, Columba Press).

Ó Súilleabháin, Muiris, Downey, Liam & Downey, Dara, 'Antiquities of Rural Ireland' (Wordwell, 2017).

Nugent, Louise, 'Journeys of Faith, Stories of Pilgrimage from Medieval Ireland' (Columba Books, 2020).

Note on the Sources: Regarding the specifics of St. Colmcille's Well, John Bradley's article proved extremely useful, and a great deal of my article is drawn from it. Noel French's book is also excellent, a useful gazetteer providing interesting information, including folklore and photographs of Meath's Holy Wells. Many of the referenced 19th Century works have been digitized and are available to read online for free.