Irish Passage Tombs: An Introduction

An introduction to Irish Passage Tombs, typology and features. Newgrange and beyond!

I am very blessed to live in the Boyne Valley, home to a fascinating range of antiquities, not least among these are the world-famous passage tombs at Brú na Bóinne, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In the future, at some point, I hope to post some articles about these passage tombs. For now, I hope the following article will serve as a general introduction for readers to the Irish Passage Tomb.

Passage tombs are the most spectacular and well-known examples of megalithic tombs in Ireland. Simply put, they consist of a stone lined passage terminating in a chamber, with the whole structure being covered by a cairn or mound of earth or stone (or both), usually encircled by a kerb of stones (Ó Ríordáin 1968, 66). However, within this broad definition there is a great diversity in size, shape and features, ranging from the small and plain to the large and elaborate and much in between (Shee Twohig 2004, 35). Hensey proposes three catagories of passage tomb:

Type I: Type I tombs are of a simple form, typically having a short passage that doesn't reach the surrounding boulder circle/kerb of upright stone (Hensey 2015, 25). The chambers are quite small, typically not large enough for a person to enter and tend to be plain. Numerous examples of Type I tombs can be seen at Carrowmore in Co. Sligo. These tombs are typically found by the coast in the north-western and north-eastern parts of Ireland, with examples having been recorded around the coast in counties Mayo, Sligo, Donegal, Antrim, Dublin, Wicklow and possibly in the Boyne Valley. It cannot be ruled out that others existed elsewhere but have been destroyed and lost (Hensey 2015, 26-27).

Type II: Type II tombs are larger, most with an 'external diameter between 15 and 40m' . The cairn usually has a horizontally laid stone kerb. A fundamental difference to Type I tombs is that Type II tombs are large enough to enter with a passage leading to a chamber. These are the most common type of passage tombs, making up approximately 75% of the total (Hensey 2015, 30).

Type III: Type III tombs are the largest, most spectacular, most sophisticated, most decorated and ornate examples of passage tombs. (Hensey 2015, 95). Examples of this type are by far the most well known. The famous examples in the Boyne Valley, Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth are Type III tombs.

While not the most numerous type of megalithic tomb in Ireland, passage tombs are relatively common with an estimated 236 examples of passage tombs across Ireland (out of an estimated total of 1,600 recorded megalithic tombs) (Waddell 2010, 63).

Passage tombs are not unique to Ireland. They are found across Western Europe (Ó Súilleabháin, Downey & Downey 2018, 317). Examples can be found in the Iberian Peninsula, Britain, Denmark, France and Sweden (Shee Twohig 2004, 48). They are quite hard to date accurately but the consensus is that passage tombs were constructed from roughly 4000 to 2000 BC (Waddell 2010, 63). The two most famous examples of passage tombs in Ireland, those at Newgrange and Knowth Co. Meath, have supplied radiocarbon dates in the range of 3500 – 3000 BC, but activity at the sites continued for many generations afterwards ( Shee Twohig 2004, 47).

Out of the 236 examples of passage tombs in Ireland, the majority are predominantly located to the north and east of the island, with some 63% of passage tombs located within a 30km wide band from the mouth of the river Boyne in Co. Meath to Co. Sligo (Shee Twohig 2004, 40). A notable characteristic of the distribution of passage tombs is the fact that there are a number of ‘clusters’ or groups of tombs. These concentrations are referred to as ‘cemeteries’ (Ó Ríordáin 1968, 68). Often the cemetery can consist of one large tomb, with satellite tombs surrounding it, such as is the case at Knowth Co. Meath. There are four main examples of passage tomb cemeteries in Ireland: the Boyne Valley and Loughcrew, both in Co. Meath, and Carrowmore and Carrowkeel, both in Co. Sligo. The tombs at each of these sites number between 12 and 60 (Waddell 2010, 65). There are also smaller cemeteries, such as that at Kilmonaster in Co. Donegal, or sometimes passage tombs survive as lone examples, such as the ‘Mound of the Hostages’ at the Hill of Tara in Co. Meath (Cooney 1997, 7).

The physical topography of the location of passage tombs varies considerably, from spectacular mountain/hilltop locations offering a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside (such as at Loughcrew, Carnbane East, the highest point in Co. Meath) to not far above sea level (Ó Ríordáin 1968, 69). The majority of passage tombs, roughly 58%, are located below 150 meters above sea level (Waddell 2010, 63). They tend, however, to be located on ridge or hilltops giving them some degree of prominence over the surrounding landscape, even if the ridges or hills themselves are not particularly large (Ó Ríordáin 1968, 69).

The first noticeable feature of a passage tomb is the roughly circular mound (or cairn) that covers it. There is some variation when it comes to mounds, in the size and material of construction. The mound at Newgrange Co. Meath is a large example, which has a NW-SE diameter of 78.6 meters and a NE-SW diameter of 85.3 meters (O’Kelly 2013, 21). Other mounds are quite small, such as the ‘Druid Stone’ in Co. Antrim which has a diameter of around 10 meters, but the majority of passage tombs have a diameter of between 10 and 25 meters (Waddell 2010, 63).

Mounds can be constructed of earth or stone, or a combination of both. The mound at Newgrange Co. Meath was constructed of layers of earth and medium sized water-rolled stones (O’Kelly 2013, 21). Mounds are usually encircled or contained within a kerb of large stone slabs called kerbstones or sometimes by dry walling (Shee Twohig 2004, 38).

As one enters the mound, they find themselves in a, generally narrow, passage. Like with mounds, there is a degree of variance when it comes to passages. The length of the passage can range from only a couple of meters to others which are very long, such as that at Knowth Co. Meath, which has a length of around 40 meters (Shee Twohig 2004, 35). The passages themselves are constructed of large upright stone slabs, roofed over with other slabs. The upright slabs (or the walls of the passage) are referred to as orthostats, and the horizontal roof slabs are called lintels (Shee Twohig 2004, 35). The size of the slabs themselves can vary also. The slabs at Newgrange Co. Meath have an average height of 1.5 meters with some being larger or smaller than this average (O’Kelly 2013, 21).

The passage, whatever length it may be, leads to a chamber. Like passages, the chambers also vary in size. They are generally circular, polygonal, subrectangular or trapezoidal in shape and can vary in size from about 1.2 meters to 6.4 meters in diameter (Waddell 2010, 65). Some chambers also have ‘side chambers’ or annexes off the main chamber. Newgrange has three of these which gives the passage and chambers an overall cruciform plan, which is somewhat of a characteristic of the most well-known Irish passage tombs (Ó Ríordáin 1968, 66). However, not all passage tombs follow this cruciform plan or even have an immediately identifiable chamber. Some passage tombs are of the ‘undifferentiated’ type where the chamber is distinguished by an increase in passage height or width, or perhaps a sill stone, rather than having a more obvious circular type chamber (Waddell 2010, 65). In fact, this ‘undifferentiated’ type of passage tomb is more common than their more elaborate and well-known relations (Shee Twohig 2004, 37). A common chamber roof design utilises a practice called ‘corbelling’, where a series of stones overlap and narrow in a dome like shape before being finally capped with a capstone. A famous example of this technique can be seen at Newgrange in Co. Meath, with the capstone placed some six meters above the chamber floor (O’Kelly 2013, 21). This design is very effective, the chamber at Newgrange remains perfectly dry to this day (Shee Twohig 2004, 37). Some other roof techniques were also used, Shee Twohig suggests that wooden roofs may have been used for some of the larger chambered examples, such as that at Fourknocks Co. Meath (Shee Twohig 2004, 37).

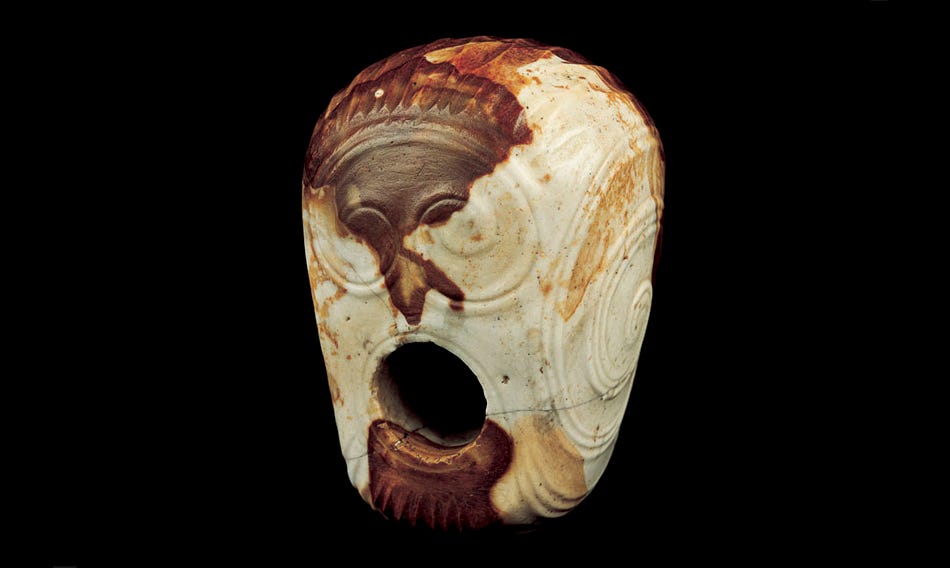

A feature common to many chambers is the location within them of large stone ‘basins’ (McQuillan & Logue 2008, 14). There is some debate over their usage but they are generally thought to have been used to contain burnt human remains (Shee Twohig 2004, 42), but, as McQuillan and Logue observe, this is not a confirmed theory and cremated remains ‘have been found on basins in only a small number of tombs’ and that perhaps there is a more ‘complex’ explanation for their function and ceremonial importance beyond simply being mere containers (McQuillan & Logue 2008, 14-15). Other 'grave-goods' have been recovered from passage tombs. Various items including pendants, stone balls, bone pins, antler pins, baked clay, quartz and pottery fragments (Hensey 2015, 101). Some 'fancier' items have been recovered from Type III tombs, such as the famous mace head (Fig 3) from Knowth.

Another feature common to passage tombs is rock art, namely carvings on the tomb’s various lintels, corbels, kerbstones, and orthostats. The designs vary considerably, with spirals, zigzags, circles, and lozenges all to be found (Shee Twohig 2004, 46). The Boyne Valley contains the largest collection of this type of artwork in Europe (Ó Súilleabháin, Downey & Downey 2018, 317) with over 300 examples found at the great mound of Knowth alone (Waddell 2010, 84). The meaning of this artwork is not clear, and although there are many theories and attempts to decipher a supposed hidden meaning, the ‘motifs used in Irish passage tombs have so far defied interpretation’ (Shee Twohig 2004, 46).

Another remarkable characteristic of some passage tombs in Ireland is their alignment with the sun at certain times of the year. The most famous example of this is at Newgrange where on the winter solstice, December 21st, light from the rising sun enters into the passage through a ‘roof box’ over the entrance and illuminates the passage and chamber. While the existence of the ‘roof box’ seems to be unique (so far) to Newgrange (O’Kelly 2013, 21) solar alignments are not. Solar alignments, usually at significant stages of the solar year (sunrise or sunset on the winter or summer solstice) have been identified and confirmed at numerous sites around the country including three in Ulster, nine in Leinster, two in Munster and one in Connacht (Prendergast 2018, 5-6).

While it is important not to overstate the prevalence or existence of solar alignments, they may give some insight into the meaning and function of passage tombs. Undoubtedly, they were what their name says, tombs in which the dead were interred. The spectacular nature of some of the passage tombs, their great size, the difficulty and length of time their construction took, the abundance of megalithic art, as well as features such as solar alignments certainly suggests a great ritual significance. The archaeological evidence of interaction and habitation at the sites for generations beyond the first builders suggests that they had continued significance and relevance beyond what might be expected for mere burial sites. (Shee Twohig 2004, 47-48). However, it remains a mystery as to the exact nature of any rituals associated with passage tombs. This mystery lends greater intrigue to these tombs and will continue to stimulate the curiosity and imagination of all visitors to these remarkable sites.

Bibliography

Cooney, Gabriel. “The Passage Tomb Phenomenon in Ireland’.” Archaeology Ireland, vol. 11, no. 3, 1997, pp. 7–8. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20558729.

“Flint Mace-Head.” National Museum of Ireland, www.museum.ie/en-IE/Collections-Research/Collection/Resilience/Artefact/Flint-Mace-Head/49d6241f-971a-466c-accc-3037de6706c1. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

Hensey, Robert. First Light: The Origins of Newgrange (Oxbow Insights in Archaeology). Oxford, Oxbow Books, 2015.

McQuillan, Liam, and Paul Logue. “Funerary Querns: Rethinking the Role of the Basin in Irish Passage Tombs.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology, vol. 67, 2008, pp. 14–21. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41220766.

Ó Ríordáin, S. P. Antiquities of the Irish Countryside. 4th ed., United Kingdom, University Paperbacks, 1968.

Ó Súilleabháin, Muiris, et al. Antiquities of Rural Ireland. Reprint, Ireland, Wordwell Books, 2018.

O’Kelly, Michael J. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend (New Aspects of Antiquity). Reprint, Thames & Hudson, 2013.

Prendergast, Frank. “Solar Alignment and the Irish Passage Tomb Tradition.” Archaeology Ireland Heritage Guide, no. 82, 2018. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26565838.

Twohig, Elizabeth Shee. Irish Megalithic Tombs. 2nd ed., United Kingdom, Shire Publications, 2004.

Waddell, John. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland. Rev. ed., Ireland, Wordwell, 2010.